alb5484834

Syria: Nestorian text in Syriac script, c.5th century CE

|

Añadir a otro lightbox |

|

Añadir a otro lightbox |

¿Ya tienes cuenta? Iniciar sesión

¿No tienes cuenta? Regístrate

Compra esta imagen

Título:

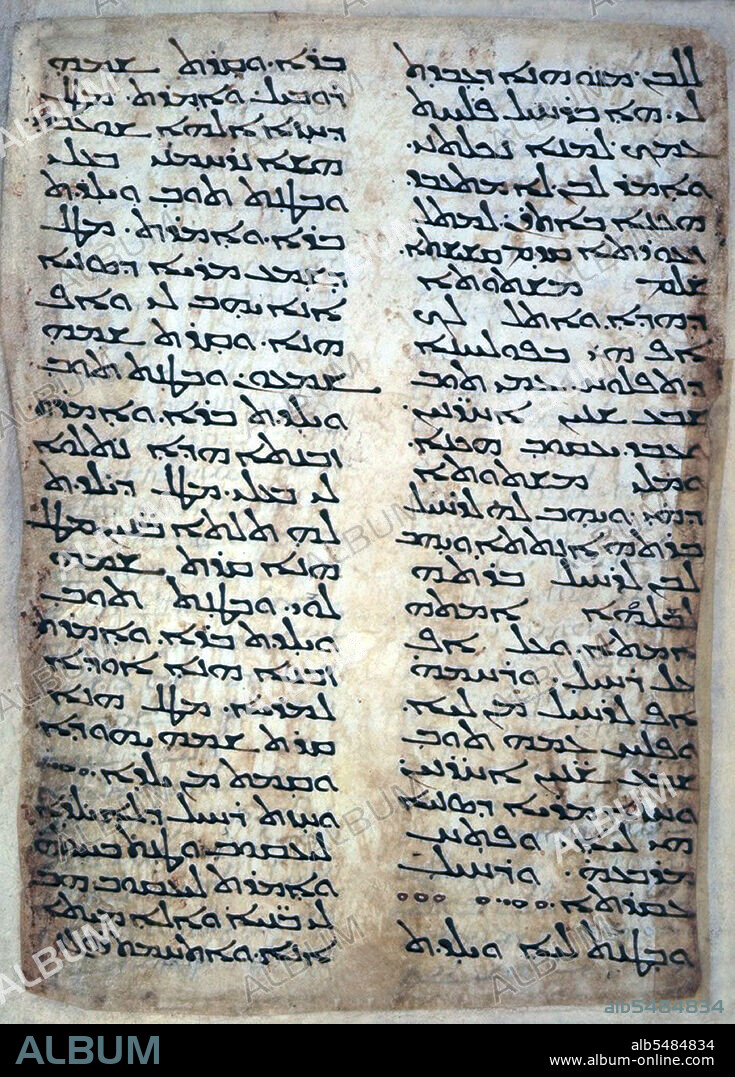

Syria: Nestorian text in Syriac script, c.5th century CE

Descripción:

Traducción automática: Nestorio desarrolló sus puntos de vista cristológicos como un intento de explicar y comprender racionalmente la encarnación del Logos divino, la Segunda Persona de la Santísima Trinidad como el hombre Jesucristo. Había estudiado en la Escuela de Antioquía, donde su mentor había sido Teodoro de Mopsuestia; Teodoro y otros teólogos de Antioquía habían enseñado durante mucho tiempo una interpretación literalista de la Biblia y enfatizado la distinción entre las naturalezas humana y divina de Jesús. Nestorio llevó consigo sus inclinaciones antioquenas cuando fue nombrado Patriarca de Constantinopla por el emperador romano oriental Teodosio II en 428. Las enseñanzas de Nestorio se convirtieron en la raíz de la controversia cuando desafió públicamente el título de Theotokos (Madre de Dios) utilizado durante mucho tiempo para la Virgen María. Sugirió que el título negaba la plena humanidad de Cristo, argumentando en cambio que Jesús tenía dos naturalezas vagamente unidas, el Logos divino y el Jesús humano. Como tal, propuso Christotokos (Madre de Cristo) como un título más adecuado para María. Los oponentes de Nestorio consideraban que sus enseñanzas se acercaban demasiado a la herejía del adopcionismo, la idea de que Cristo había nacido como hombre y que luego había sido "adoptado" como hijo de Dios. Nestorio fue especialmente criticado por Cirilo, papa (patriarca) de Alejandría, quien argumentó que las enseñanzas de Nestorio socavaban la unidad de las naturalezas divina y humana de Cristo en la Encarnación. El propio Nestorio siempre insistió en que sus opiniones eran ortodoxas, aunque fueron consideradas heréticas en el Primer Concilio de Éfeso en 431, lo que condujo al Cisma Nestoriano, cuando las iglesias que apoyaban a Nestorio se separaron del resto de la Iglesia cristiana.

Nestorius developed his Christological views as an attempt to rationally explain and understand the incarnation of the divine Logos, the Second Person of the Holy Trinity as the man Jesus Christ. He had studied at the School of Antioch where his mentor had been Theodore of Mopsuestia; Theodore and other Antioch theologians had long taught a literalist interpretation of the Bible and stressed the distinctiveness of the human and divine natures of Jesus. Nestorius took his Antiochene leanings with him when he was appointed Patriarch of Constantinople by Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II in 428. Nestorius' teachings became the root of controversy when he publicly challenged the long-used title Theotokos (Mother of God) for the Virgin Mary. He suggested that the title denied Christ's full humanity, arguing instead that Jesus had two loosely joined natures, the divine Logos and the human Jesus. As such he proposed Christotokos (Mother of Christ) as a more suitable title for Mary. Nestorius' opponents found his teaching too close to the heresy of adoptionism – the idea that Christ had been born a man who had later been 'adopted' as God's son. Nestorius was especially criticized by Cyril, Pope (Patriarch) of Alexandria, who argued that Nestorius' teachings undermined the unity of Christ's divine and human natures at the Incarnation. Nestorius himself always insisted that his views were orthodox, though they were deemed heretical at the First Council of Ephesus in 431, leading to the Nestorian Schism, when churches supportive of Nestorius broke away from the rest of the Christian Church.

Crédito:

Album / Pictures From History/Universal Images Group

Autorizaciones:

Modelo: No - Propiedad: No

¿Preguntas relacionadas con los derechos?

¿Preguntas relacionadas con los derechos?

Tamaño imagen:

3500 x 4878 px | 48.8 MB

Tamaño impresión:

29.6 x 41.3 cm | 11.7 x 16.3 in (300 dpi)

Palabras clave:

ASIA • ASIATICO • CHRISTIAN • CHRISTIANITY • CRISTIANA • CRISTIANAS • CRISTIANDAD • CRISTIANISMO • CRISTIANO • CRISTIANOS • CRISTIANSMO • CRISTO • ESCRITURA • HISTORIA • HISTORICO • JESUS • RELIGION • RELIGION: CRISTIANA • SIRIA • SIRIACO • SIRIO

Pinterest

Pinterest Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Copiar enlace

Copiar enlace Email

Email